Over the last 100 years, code-makers and breakers have gathered in dedicated institutions where they create and use the latest technologies to monitor secret communications – today this institution is called the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). For the first time ever, GCHQ have lifted the lid on a world of secret communications and the data related challenges they face today.

The Science Museum’s current exhibition showcases artifacts from as early as World War I, yet it wasn’t actually until World War II that spying and communications saw unprecedented levels of technological advancements. The infamous Bletchly Park was a key site for GCHQ to break the encryption of messages sent by Britain’s enemies. Over a million messages were decrypted at Bletchley, yet it only became public knowledge in the 70s when veterans began to tell their stories. Even today, much of Bletchly’s secrets remain unknown.

Walking through the exhibition it was clear that times have definitely changed since the days of Bletchley Park. To begin, the public’s acceptance of secrecy has changed; companies of today, whether public or private, are under public pressure to be transparent. However, often these changes have been forced by public scandal. The exhibition showcased two examples: Zircon in the 1980s and the Snowden Scandal of 2013.

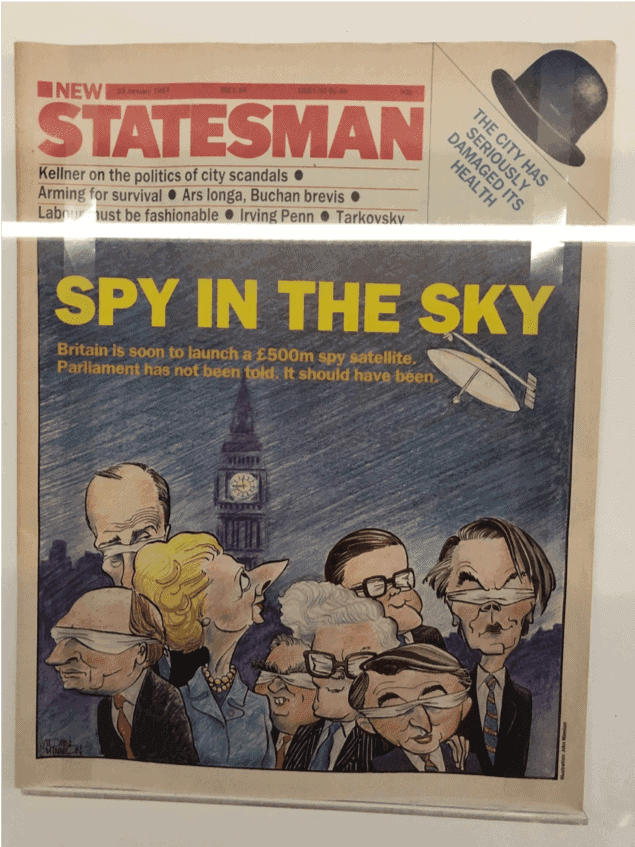

Zircon was going to be Britain’s first spy satellite. It was designed during the Cold War to listen in on secret radio messages inside the Soviet Union. However, investigative journalist Duncan Campbell revealed the details of the Zircon project in this January 1987 issue of New Statesman (a copy of the magazine is on display at the museum).

His article revealed the project’s budget had been hidden amongst other government department’s spending estimates, without political scrutiny. It also revealed some of the potential technical capabilities of GCHQ’s proposed spy satellites. The indirect consequence of this investigative journalism being that GCHQ took its first major step ‘out of the dark’.

And the second major step in bringing GCHQ ‘out of the dark’ I witnessed was in 2013, when Edward Snowden leaked documents claiming to describe how GCHQ collected personal information from millions of innocent people. The documents ignited a public debate and brought the world’s attention to a very delicate question – how do we balance security and privacy?

The Snowden leak undoubtedly changed how the world felt about cybersecurity and government intelligence gathering. In general, the justification that government agencies use across the world for snooping can be simplified into the motto: ‘nothing to hide nothing to fear’. However, for ordinary citizens, this statement instils fear rather than a sense of security. People feel as though an unnecessary amount of trust has been given to intelligence agencies. Where though do private companies fit into this debate? A scandal such as Cambridge Analytica in 2018 does raise the question over the relative ‘snooping’ capabilities that a public organisation has in comparison to a private company.

I listened to GCHQ admit that they have the capability to build a very accurate profile on any law-abiding citizen; but why do the likes of Facebook and Google not face the same level of inquiry when they have the means to build a profile with a similar level of accuracy? Currently, there is a demand for more privacy combined with the expectation of enhanced security; but is it a realistic goal when companies and organisations have the access that they do? Does it have to take a public scandal like Cambridge Analytica to expose inadequate privacy protection policies coming out of multinational corporations?

Looking to the future though, by 2024, the collective cost of data breaches is set to reach $5 trillion. The sooner that an organisation realises that cybersecurity losses are a cost of doing business in the digital age, the easier it will be to safeguard against the worst-case scenario.

Finding the appropriate balance between security and privacy remains a slippery task for both private and public organisations. However, if you can anticipate what the future will bring, you can better prepare your organization for the worst. It may just keep you from contributing to 2024’s $5 trillion in data breach fines or from being a victim to cybercrime. So maybe it’s time to ask, what steps has your business taken to deal with the data-related challenges of today and prepare itself for the challenges of the future?